How One Man Helped to Re-Enfranchise Almost A Million Floridians

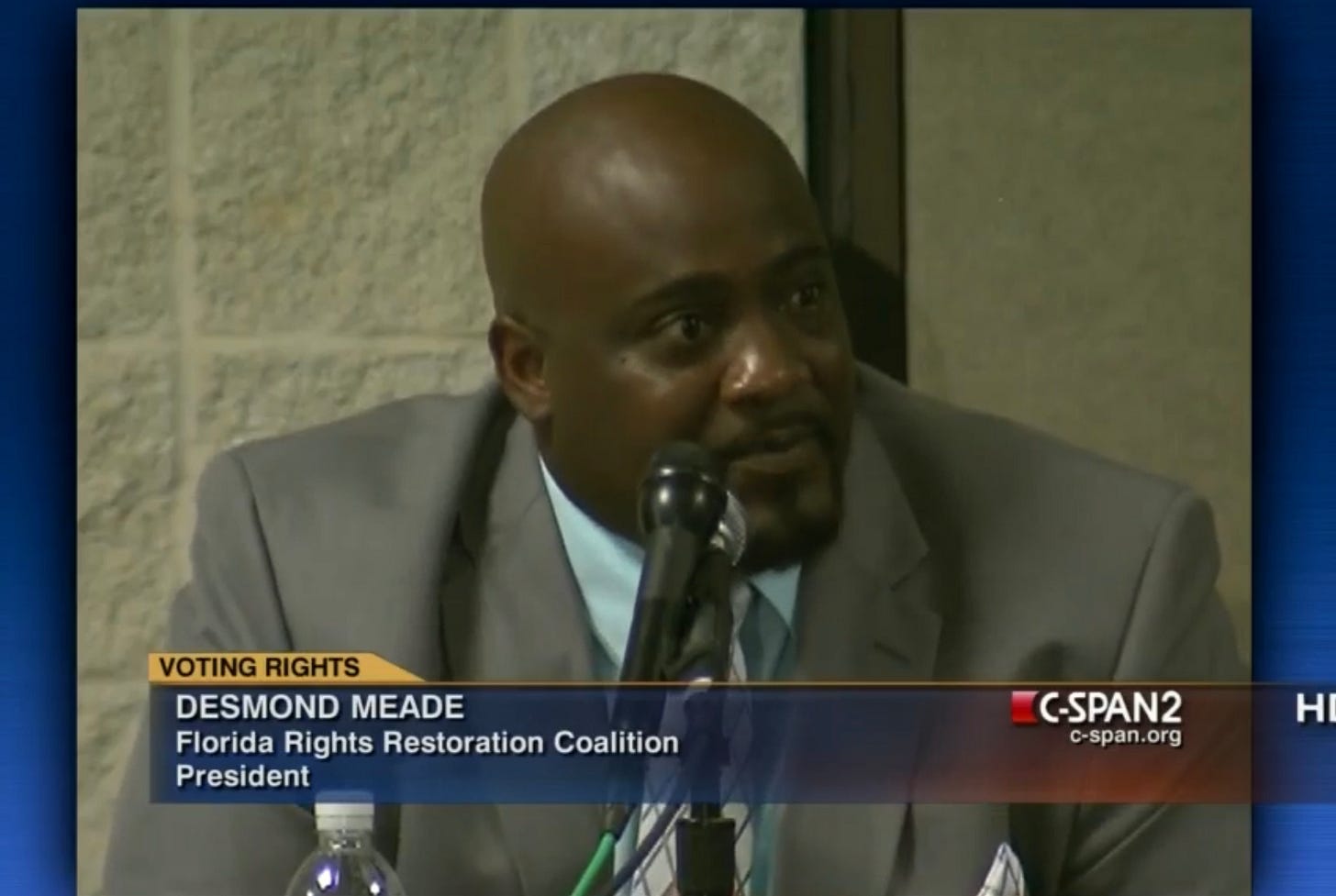

Want to be inspired? Take a moment to learn about Desmond Meade.

Desmond was, quite literally, at the brink. Standing on a railroad track on that fateful day in August 2005, he was determined to have a train hit him and take his life. He was homeless, a drug addict, and had multiple felony convictions, and he didn’t know how he could keep on living.

But the train never came. He walked away and checked himself into rehab. And he began to change his life.

Amazingly, he went to college and then law school. But because of his felony convictions, he could not sit for the bar exam or participate in the most fundamental aspect of being a citizen: under Florida law, he was not allowed to vote. Indeed, Florida took away voting rights for life for people convicted of a felony, which included an estimated 1.4 million people in the state. The effects of the law had a disproportionate effect on minority individuals given the reality of the criminal legal system.

Meade set out to change that law.

Through the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition, an organization he has led since 2009, Meade began to advocate for an amendment to Florida’s constitution that would re-enfranchise people with a felony conviction who have completed their sentence (except for those convicted of murder or sexual offenses). He told me, during our interview on the Democracy Optimist podcast (listen here), that the process to put the initiative on the ballot was slow and took quite a bit of effort. For example, he recounted how he drove over 50,000 miles all over the state every year to discuss re-enfranchisement with anyone who would listen.

Finally, his efforts for what became known as Amendment 4 were fruitful: Meade and the FRRC obtained over 800,000 signatures in support of the measure. In 2018, the state’s voters approved the amendment with just under 65% of the vote, well over the 60% they needed for passage under the Florida Constitution. Meade noted that the amendment’s supporters were widely bipartisan, and that, ironically, many more people voted for the amendment than for Governor Ron DeSantis, who was elected that same year.

But the fight for voting rights is never over. The Florida legislature sought to minimize the impact of Amendment 4, passing a law that required individuals to pay back all fines and fees associated with their conviction before they would regain their right to vote. However, in many cases, the state could not even tell the individuals how much they owed, as there is no central database with this information. In addition, the amounts due had skyrocketed because the state assigns debts to private collection agencies. The New York Times explained the various intricacies of this system in an article titled “When It Costs $53,000 to Vote”; the title references just one example of the many prohibitive amounts assigned to returning citizens. Amendment 4 was supposed to re-enfranchise around 1.4 million individuals, but because of the legislature’s maneuver—which a federal appeals court upheld—the effect was much smaller. Still, around 700,000 people regained their right to vote, which, as Meade said, is still a significant achievement. Florida was the state with the most disenfranchised voters, both by raw numbers and by percentages, and Amendment 4 was the largest expansion of voting rights in half a century.

Yet Florida continues to lead the nation in the disenfranchisement of those with a felony conviction. According to the Sentencing Project’s 2023 review of Florida’s disenfranchisement, most of the state’s disenfranchised voters are people shut out by the legislature’s law that limited Amendment 4.

There is, however, still a silver lining in this story. Desmond Meade’s efforts to make a difference in Florida show that meaningful progress on voting rights is achievable. Many states are debating the issue of felon disenfranchisement and are easing their laws. Maine, Vermont, and DC never take away the right to vote and democracy still works in those places. Other states now give back voting rights once individuals complete their sentences. Deb Graner, as I discussed in a previous post, is now a leading voice on this issue in Kentucky. And the reforms in multiple states have generally been bipartisan.

Sometimes all it takes is just one individual to stand up for voting rights. Substantive progress is possible anywhere, and the fight to protect the right to vote continues to be alive and well.